Haunted & Haunting: An Interview with Zack Pieper

by Gina Myers

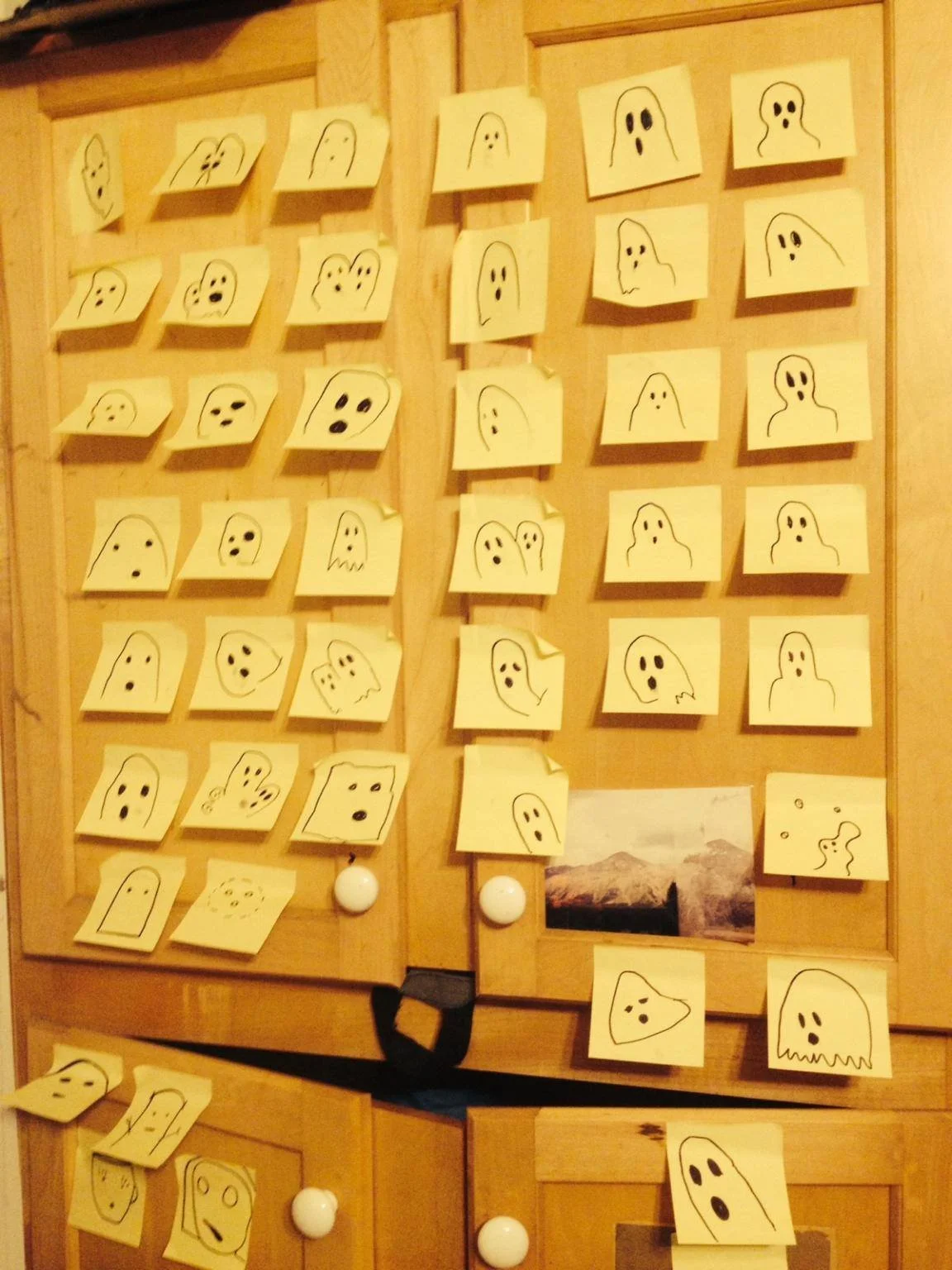

Ghost-It Notes at The Triangle, Milwaukee, WI 2015

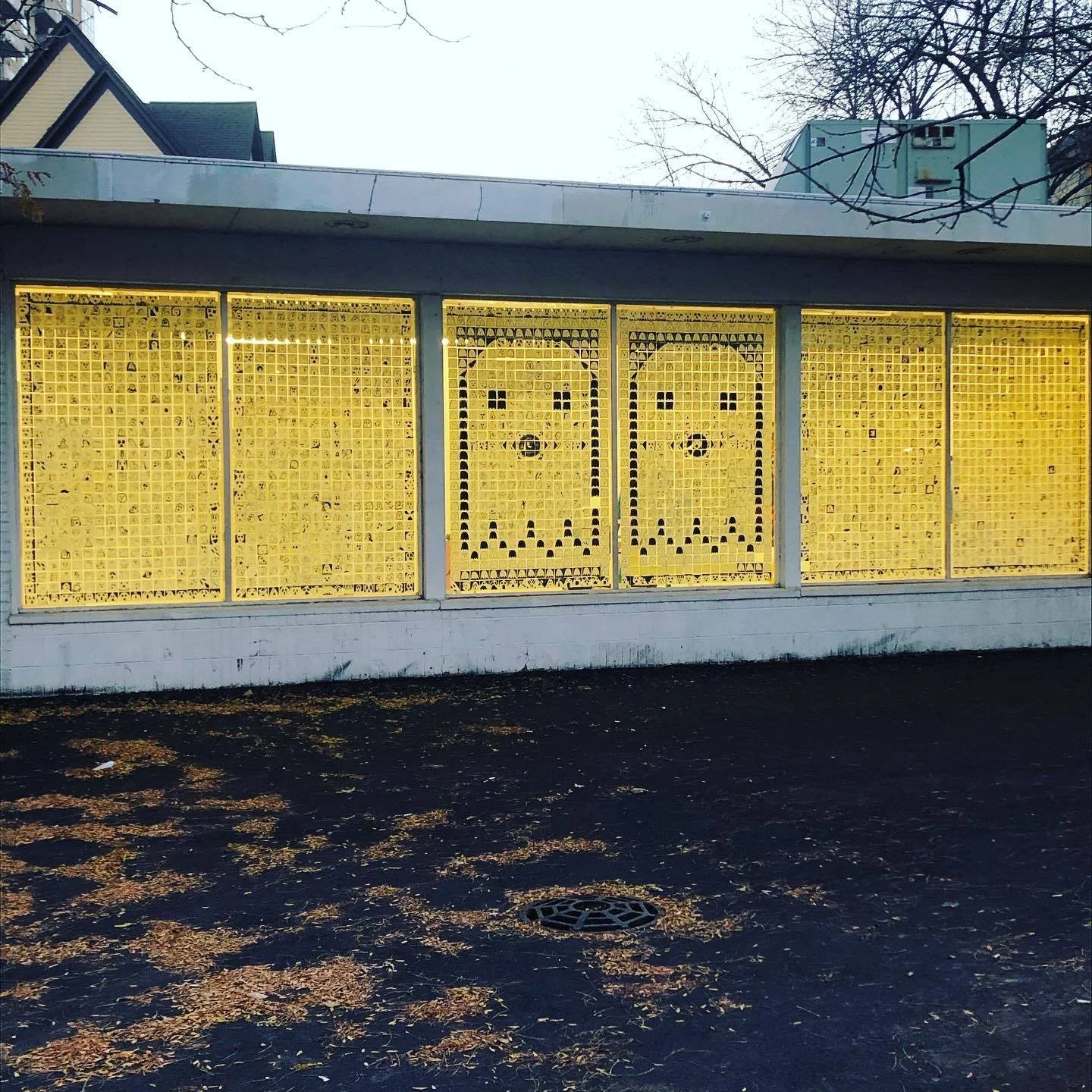

Each October select storefront and gallery windows in Milwaukee, Wisconsin fill up with ghosts. Or perhaps these windows are regularly haunted, but for nearly a decade now the haunting also manifests in an annual installation of post-it note mosaics consisting of drawings of ghosts. Behind these hauntings is poet and musician Zack Pieper, who draws thousands of ghosts each year for this project, which has now begun to spread to other cities as well.

Pieper's work spans poetry, performance, radio, visual art, and song. Same Here, selections from a decade of poems, was released by Adjunct Press in 2019. Poems and writings have appeared in Blazing Stadium, Bright Pink Mosquito, Disappearing Book Series, The Milwaukee Anthology, and elsewhere. He's performed at Detroit's People's Biennial at MOCAD, and for The Brooklyn Rail's “New Social Environment” series. He is the host and curator of ECLOGUES, a program of radio plays and sound art, and is the co-founder of Activities, an archive of tapes, albums, videos, songs and sound experiments spanning several decades of midwest-affiliated musicians and multidisciplinary artists.

Pieper recently discussed his annual installations with CDSOB’s Gina Myers via email.

Before I became aware of your ghosts project, I knew you primarily as a poet and musician. Have you always practiced visual art, or is this something you picked up in more recent years?

Yes, I've always made collages, assemblages, drawings, doodles, little book covers, or album covers—sometimes in connection with poems or songs, sometimes just because. I suppose I do consider myself (if anything) primarily a poet, but hopefully in a broad sense, maybe like in that old Greek way: poiesis—to make. I'm just a maker, compulsively so. Songs, plays, movies, paintings, various arrangements across various mediums—can all be kinds of poems, contain poems, or “have poetry” to them, obviously. Maybe some works are even like adjacent structures, or just different rooms, in the same big old haunted house of poetry. But I've always used whatever form—or medium—was laying around. I like to use common and ubiquitous materials.

How did your ghost project initially come about?

Y'know, I'm not really sure. I didn't consider or consciously pursue conjuring ghosts, it was just something that came to me, and started as a yearly ritual—“harvesting” all these ghosts, drawn on post-it notes—beginning roughly 9 years ago. It started as a personal exercise. Perhaps partly as a purgation (exorcism?) of common visual gestures and tropes. A sort of automatism, too. These ghosts are one of those projects that just took over, compelled me, almost commanded me, and did not stop. Apparently, they will not let me.

Real Tinsel, Milwaukee, WI, 2021 Photo: Nicholas Mira

You say the ghost project began as a personal exercise—how did you come to eventually showing it/making it a public art project?

Well, in the first "visitation," I was doodling in magic marker in the kitchen, per usual, and unconsciously made a ghost-shape. Then I just felt compelled to keep doing them. I filled the kitchen, cabinets, appliances, TV screen. I filled a bunch of interiors. Then it dawned on me: ghosts appear in windows. They need to be framed by some place. Riverwest Radio, a community-run radio station in Milwaukee, has big shop front windows. So, first I filled their front windows with ghosts in 2013. They looked right that way: all lit up, at night, and in the early dawn.

Since then, it's been mostly public spaces: art gallery windows, shop fronts, my own apartment windows one year. For a few years, I produced “ghost-its” for an annual Milwaukee multi-location art event called “Ghoost Show.” These ghosts will continue to appear in public settings. It's terrific to get to know different little businesses, community hubs, and various neighborhoods this way. Sometimes certain residents will drop by to check in on the progress throughout. Occasionally, a random passing kid will ask to draw a ghost.

For some passerby, the ghosts function as a kind of Rorschach test. Someone might stop and linger, scanning the windows, and suddenly “find their ghost,” or recognize something or someone in a post-it, and I'll overhear: "This one's Jake! Oh, that's totally Jake." That's when I know I can stop arranging them; I can disappear. They are in the right places and have reached a configuration that invites a stranger's recognition and projection. Working in public forces you to remember this is for anyone.

Can you tell me a little about your process? When do you begin working on this project each year?

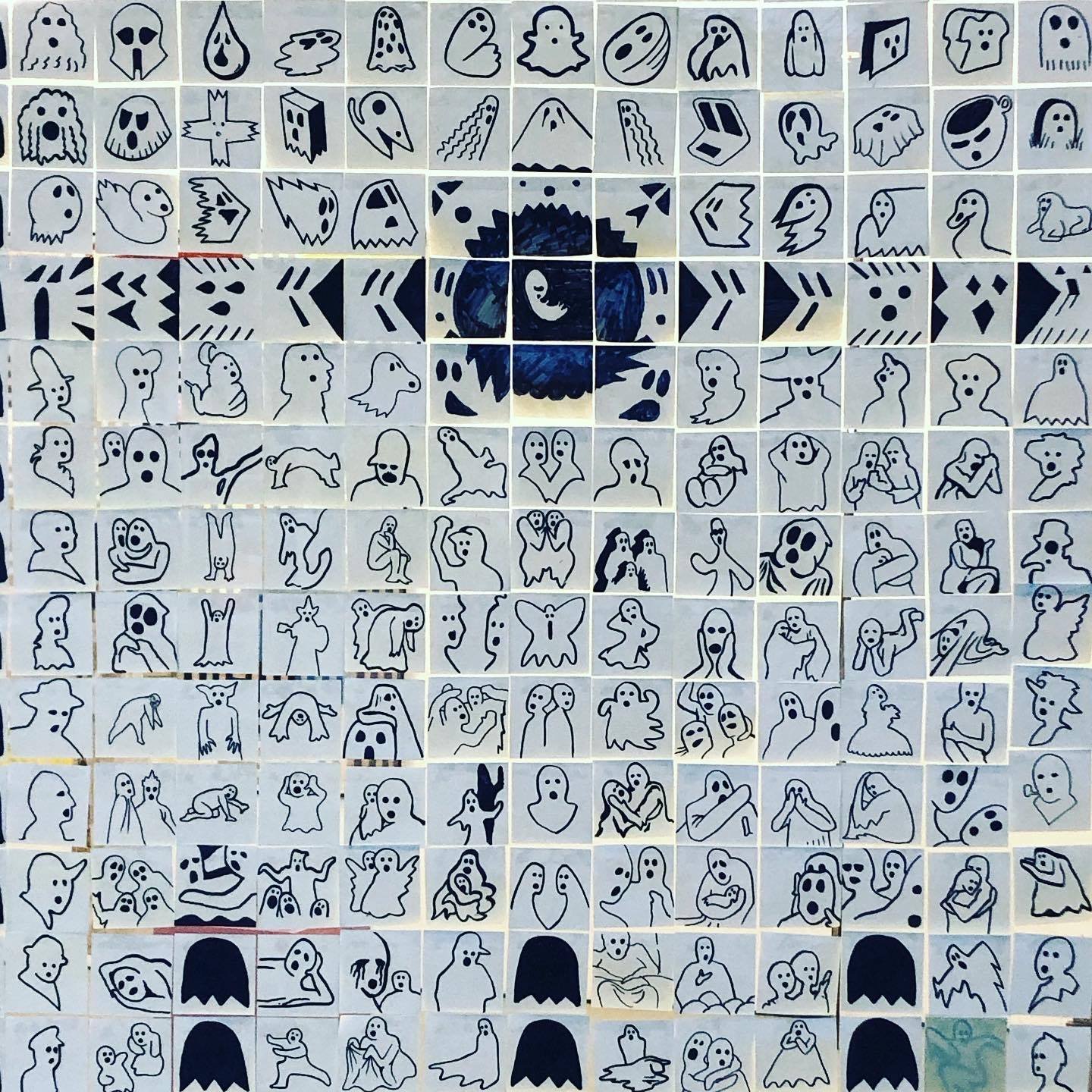

The process is somewhat unconscious. Maybe necessarily so. I don't always notice I'm engaged in it. I might have something close to hypergraphia, and am almost always compulsively drawing and writing things down on envelopes, scraps of paper, little notebooks. Throughout the year there will be a slow trickle of them, small batches of ghosts here or there. When I catch an image in a magazine, or scrolling through pictures, I might find a shape or figure and “ghost it”–just catch its outline, its compositional essence. It almost feels like finding something hidden. I like to think of that Hank Williams song: "Pictures From Life's Other Side." Some come from quotidian life, from dreams, family photos, newspapers, comic books, picture bibles, advertisements, whatever. Some are tied to specific memories, memories of loss or of intense emotional states. Others are more abstract: symbols, icons, or glyphs. Images that stretch representation. I keep all these post-its archived in large, heavy books.

The ghosts accumulate faster and faster, and with more impetus, a few months before the set date of the installation, or “haunting.” By September, I am drawing very large batches of them, almost non-stop. Anywhere, on the bus, or all-night sessions, for hours, almost in a sort of trance. Sometimes, during the installation process, as I'm putting the ghosts in the windows, I'll realize I have no memory of drawing many of them–at all! None whatsoever. Which can be nice. They are trying to surprise me too.

About how many ghosts do you draw for an installation?

The number of ghosts varies depending on a space's dimensions. The largest amount of post-its a space has required was this past year, at roughly 5,400 ghosts. I try to do at least 1,500 to 2,000 new ghosts every year. In 2020, at The Green Gallery, I did 3,500 new ghosts. Certain motifs always return. Ghosts from previous years will pop up, or seem to lend themselves, and I'll reuse batches sometimes, sprinkle them in. But I take a smidge of pride that a little more than half the ghosts are always fresh ghosts. Every year. That's a guarantee.

Interior Detail of Ghost-It Notes, Milwaukee, 2013

This past year, I know you had more than one installation with at least one in Milwaukee and one in Baltimore—how did that work? Did your ghosts travel with you, or did you create them after you traveled to Baltimore?

I wouldn't have had enough time to draw that many ghosts for all those Baltimore windows while there; it wouldn't be physically possible. So I took some from Lion's Tooth bookstore in Milwaukee (which is a lovely, intimate space) with me. But I had many also set aside for Baltimore. Each haunting and each arrangement is unique.

As often happens, I'll have a rough idea planned for a certain window. Then, once I spend time in that specific space, start putting them up in the windows, and feel them all staring at me, I might realize suddenly: something is off. Or rather, is too “right.” I'll need to come up with a different idea, fast.

So improvisation is often essential for it to work. It needs to feel as though they are arranging themselves almost of their own volition—which can be nerve-wracking. This happened in a few windows in Baltimore last year. And I must say, I was lucky in that LieAnne Navarro, an artist and curator at Cotyledon Arts–an exciting organization also involved with facilitating sustainable living for artists–was extremely patient and accommodating to the project's occasional difficulties.

But, yeah, I do end up drawing some on the spot. I might notice certain ghosts are not retaining that “separateness and togetherness” they need, like certain molecules needing certain proximities for cellular growth. That kinetic push and pull. So I'll quickly dash off more to make others around them have a different weight or upset the arrangement from feeling too “fixed.”

Posting them up in the windows is a separate set of demands. Things can get difficult. It's always fun if a friend drops by to help trace a few border ghosts, or helps keep certain rows of post-its straight. But mostly, I am alone for extended periods.

Haunting these places is a strange experience; it's isolating, tedious, and can be physically demanding. But it also becomes ecstatic, even euphoric, gradually. Like trying to do a magic trick in an aquarium. A bonus is that I get to disappear, behind the glass of the windows, ever so slowly, as the ghosts take my place, one by one.

Can you tell me more about your concept of “haunting”? What does it mean to you to haunt or be haunted?

Haunting is a metaphysical concept, and so, a broad one. For my project, it's partly that colloquial sense of it, as in a haunt: a store, a shop, a bar, a restaurant, a place where one hangs out, inhabits regularly, as part of a human or social reality—as well as all the obvious thematic and cultural resonances. After days on end of ghosting in the windows of these places, sleep-deprived, you start to lose yourself, you go on a kind of auto-pilot, and become a ghost yourself, haunting the space and its neighborhood.

There is also something haunting to me about the transfixion on novelty. That need for utility, but also surprise. The novelty of ritualistic adornment, the adornment of landscape and how a place becomes alive–a site of projection and reception. The commodification and distortions of traditional iconography, the tourist-trap tropes of haunted houses, hotels, and hayrides, also play into these themes and the formal novelty of haunting. A friend told me he likes how the ghosts force you to experience them outside of these spaces, to see them all lit up. Someone said "it's like a pop-up cathedral." Fair enough. Illumination requires a degree of novelty.

The sacred and the novel are often closely related. Poet Jack Spicer once pointed out (half-disparaging poetic “tricks”) that “silly” also means “blessed” in Old English. In most lore, sacred places are marked by miracles, supernatural occurrences, and such disturbances in a place's normative “utility,” etc.

Ghosts are elemental, the limit of our individual consciousness. So there's the religious element to haunting that extends throughout the record of human myth. In the Christian Gospels there is The Holy Spirit, or “Ghost” as the manifestation of divine inspiration. There's the jinn of Islam, and the preta, or “hungry ghosts” of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism, often spirits of the greedy, selfish, and materialistic, condemned to have needs so bottomless they are never satiated. The Surangama Sutra, names ten types of ghosts, the nature of their haunting all defined by the features of their particular vice while alive. It's a “punishment suits the crime” bit. There are obviously diverse examples everywhere, and I entertain them wherever I encounter them.

Haunting is also tied to a physical place's memories, and the landscape's attendant personifications of loss, anguish, bereavement, longing, and vengeance. Cross-culturally, there's a commonality to ghosts being vehicles of justice, or retribution, particularly at the sites of past massacres or colonial devastation. Ghosts of justice tend to be tied to a larger historical dimension, as history's narratives are often at odds with the actual shaping of a landscape and the ruthless exploitation of its resources and various inhabitants. I've been reading Alicia Puglionesi's sprawling book In Whose Ruins: Power, Possession, and The Landscapes of American Empire, which locates various sites of "haunting" from examples in American expansionism and the commodification of various Indigenous peoples' beliefs in the drive for economic domination, or in the service of technological advancement. Puglionesi writes, "We have to go down the obscure paths of haunting and damnation to become unsettled, to recognize the landscape not as a canvas of endless opportunity but a dense layering of desires, strategies, betrayals, and resistances." Haunting can exist in relation to what has been suppressed in a historical narrative, or a continuity disrupted, and stories of haunting are often a means towards giving a landscape its own sense of agency. Along with Puglionesi's book, I'd also recommend Avery Gordon's Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination for more historical examinations of haunting, and its relationship to landscapes, both urban and rural.

There's a lot to think about in the psychological dimension of haunting too. Everyone has a ghost. Often the power of the haunting will depend on the degree to which it has been suppressed in our collective or individual psyches. I remember Henry James' old story "The Jolly Corner" gets at this–a consciousness pressed against the reality of all it did not do, all it did not become. The features and contours of a particular absence, of all that could have been or should have been. Whatever is hidden, is buried, is forgotten unjustly, are all conditions that could indicate haunting. The discord between some idea of “natural law” and “man's law.” The subversion and transgression of fate.

I've always been haunted by this phrase by Rimbaud: "A chaque etre, plusieurs autres vies me semblaient dues," or "For each life, it seemed like several other lives were due."

I think of these things whenever I finish an installation, often very early in the morning, and find homeless or displaced people from the neighborhood checking out the ghosts.These individuals and communities have several times been the work's first audience upon completion, and their interest and appreciation is particularly meaningful to me.

Most art is a kind of haunting, in that it tries to evoke a presence, or presences, and stop time.

The Green Gallery East, Milwaukee, WI, 2020

Cotyledon Arts, Baltimore, MD, 2022

Ghost-It Notes at Riverwest Radio, Milwaukee, 2014 Photo: Wendy Jean

What, if anything, has changed for you about this project over time?

I suppose I'm fascinated by holiday decorations or seasonal rituals. Or rather, that’s the medium I'm working in, haha. I'm drawn to Halloween, All Saint's Day, or Día de los Muertos, The Ghost Festivals of China, as well as the interpretive aspect of various ceremonies, the marking of time through a collective activity done in a multitude of idiosyncratic ways. I'm interested in the sameness in disparateness, and the disparateness in sameness.

The ephemeral and cyclical nature of the project is what makes it work, I hope. The ghosts often can't stay for too long in each year's space, often for practical reasons, and are always made with just dollar store office supplies. They are here and gone, as it should be. For that reason, not much has changed in terms of approach. Styles of individual ghosts, or batches of ghosts, of course, will vary in tremendous ways, infinite ways, and continue to morph and change. But never the concept, the occasion, or the materials. At least not too much.

I learn new things each year about the alchemy of images and the different spaces they inhabit: their combinations and recombinations, the need for each ghost to feel inexplicably both alone and of a piece. It's rewarding to explore and inhabit different neighborhoods and I hope to continue traveling to haunt various spaces until I expire. Unfortunately, ghosts seem to swarm around bad puns—but it's true: by the end of every year's installation/haunting, I do feel more like I am their medium, than vice versa.

Are you currently at work on anything else right now?

I'm currently finishing up editing a very large manuscript of hundreds of small “poem portraits” called CAMEOS. I've been writing these for years, and they relate a bit to the practice of making ghosts. At least in a formal way.

I'm always attempting things with sound recordings and songs, and am currently working on a radio play about Caedmon (sort of), the hayseed poet from Bede's History who was instructed in a dream to sing a hymn of creation, and (I think) the voice of an alien disguised as an angel. It's called “Earth Angel.” The hymn keeps distorting and changing, like a long game of "telephone."

Poems written for a voice out loud or in one's own head, and the page (or the screen), are always going on too.

Following the theme of doing seasonal decorations, and mosaics, or tapestry-type work: I've been saving thousands of multi-colored dollar signs, cut out from junk mail and advertisements, to cover someplace in the future. Maybe a hearth. These might be appropriate for a Christmas mosaic.

I'm also working on just staying afloat, using my life, trying to be useful. And as always, I'm preparing for next year's harvest of ghosts, and finding the right spot to haunt. My dream is to have thousands of ghosts haunt an airport someday. At this point, they've come to expect a brief spotlight. Some ghosts are divas.

View more ghosts on Instagram at @zack_pieper. To propose future ghost installation locations, please contact zdpieper@gmail.com.

Detail from The Green Gallery East, Milwaukee, WI, 2020

Yours Truly Gallery & Studio, Milwaukee, WI, 2019

Lion's Tooth Bookstore, Milwaukee, WI 2022

Ghost Tag (Alley), Milwaukee, 2014

Detail from The Green Gallery East, Milwaukee, WI, 2020

Globe Coffee, Baltimore, MD, 2022

Cotyledon Arts, Baltimore, MD, 2022

Cotyledon Arts, Baltimore, MD, 2022

Detail from Cotyledon Arts, Baltimore, MD, 2022