Friday Feature

Each week “Friday Feature” brings you a mini-review of a horror movie, book, album, or other cultural artifact. Have something to contribute? Email the editors at culdesacofblood@gmail.com. View the archive of past Friday Features.

Now considering: Pamela Vorhees’ sweater in the 1989 Nintendo Friday the 13th game

Pamela Voorhees’ sweater in the 1989 Nintendo Friday the 13th game

Sorry, Freddy, but for me, the most iconic sweater in horrordom—nay, filmdom—will always be the one worn by Pamela Voorhees across the Friday the 13th series. (Although Chris Higgins definitely gets points for her electric blue number, which may be the reason Pammy pops up to get her hands on it at the end of part 3.)

That said, my favorite version of Pamela’s pullover isn’t the classic gray version. Instead, this neon (demon) lover has always championed the pixelated perfection of the sweater as depicted in 1989’s Friday the 13th Nintendo game.

Yes, yes, gallons of internet ink have long been splashed, Jason-versus-a-sleeping-bag style, over how notoriously terrible this game was… before even more was tsunami’d, Jason-versus-NYC-sewers-toxic-waste style, over how incredibly underrated this game actually was. The latter take is correct, and this game deserves a place of honor as a pioneering survival horror classic.

In the game, you switch between six counselors who travel around Camp Crystal Lake, searching for weapons and resources while fighting off a variety of monsters from the famous franchise, like a bright purple and periwinkle Jason and, you know, wolves. You have the option to venture into a cave, where you can tackle a side mission: Destroy Pamela… if you can!

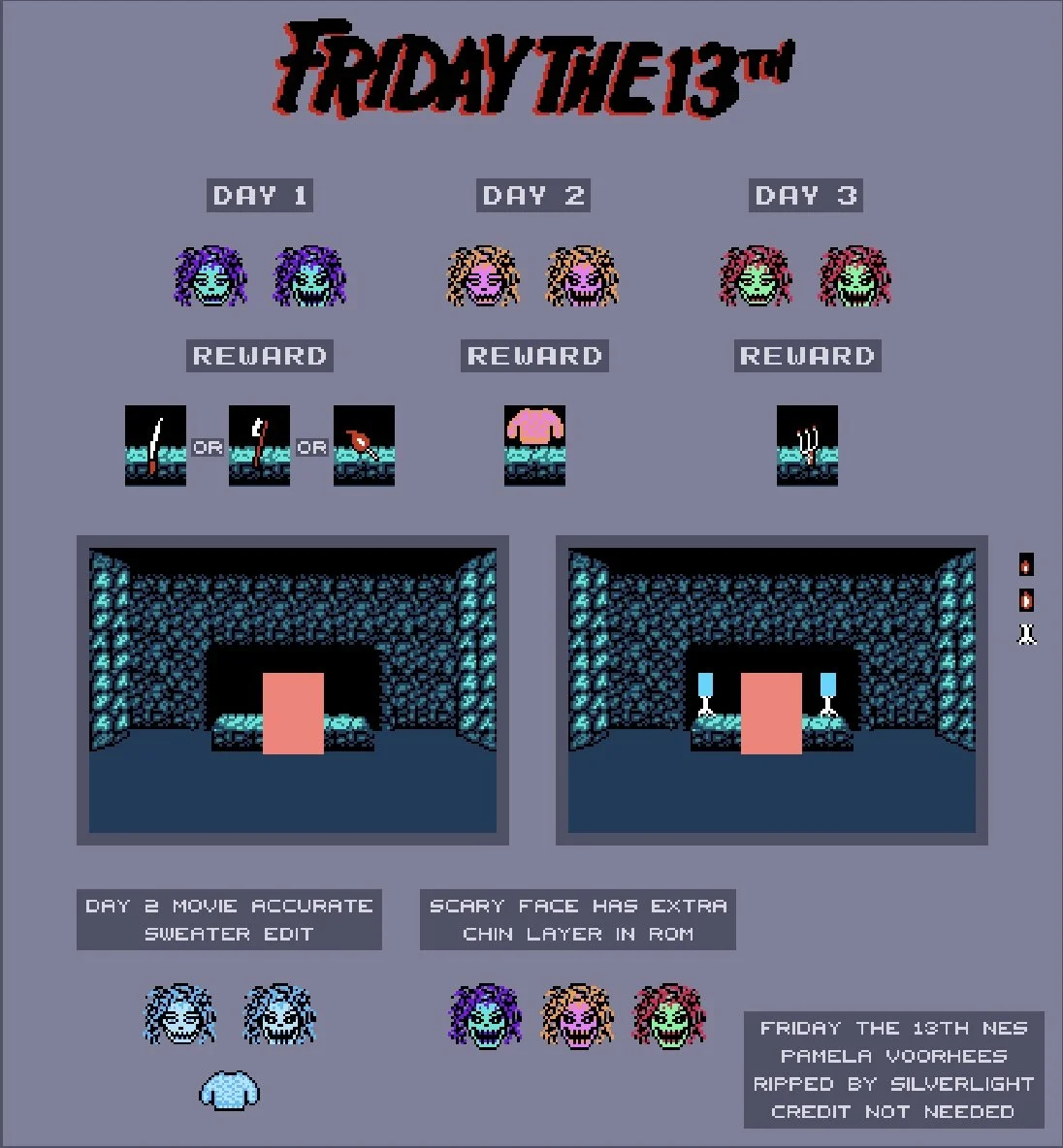

But this isn’t our blonde Betsy Palmer from the films, I’m pleased to report. This Pamela, who happens to be a flying sentient severed head, has gotten a much-welcomed New Wave makeover. On each of the three in-game days where players can face her, Mrs. V shows up with a face/hair color combo that’s either 1) Prince-inspired computer-blue/ Purple Rain, 2) Pepto Bismol and melted sherbet, or 3) sea green and magenta.

Just gazing on her beauty as she flies around the screen attempting to murder you should be reward enough, but if you defeat her on the second day, you receive her sweater, which is a bold pastel orange and pink that would really have popped onscreen if only the original 1980 film’s wardrobe designer Caron Coplan, wardrobe mistress Jan Shoebridge, and wardrobe assistant Anne King had decided a full day of killing was no reason to neglect one’s kicky glamour.

The best part of all, however, is that after obtaining this sweater, your character immediately puts it on, at which point it begins flashing green and whatever Day-Glo color your counselor’s original outfit happened to be. And unlike the 2017 Friday the 13th game, Mrs. Voorhees’s sweater can be worn by all counselors, not just the women, which I think speaks to our Pamela’s tireless work to slash through any would-be gender divisions.

And while I adore this version of the sweater because I worship at the altar of Rainbow-Brite-till-ya-eyes-bleed color overload, the bigger reason is that I feel as if this video game version pays the proper respect to what I believe is the most powerful totem of the entire franchise. Sure, we all know and love the hockey mask—thanks, Shelly!—but without Pamela there is no Jason in any sense. She is the beginning, she is fury, she is vengeance.

The perfectly satisfying/satisfyingly perfect ending of Friday the 13th Part 2 shows us the mythic might of the sweater and how it represents the primal forces that danced behind Pamela’s perfectly crazed eyes. While the resourceful Ginny may tap into its magic temporarily, it’s ultimately too powerful for anyone but Pamela to fully inhabit. (Although it’s still a hell of a lot of fun to run and jump around an 8-bit Camp Crystal Lake sparkling like a Twilight vampire as if you could.)

So let’s all pay tribute to the way Nintendo depicted an icon as she deserves. Mrs. Voorhees is mother nature, so let’s honor the fact that, for those of us in the know, it’s always sweater weather. 5 out of 5 sacs of blood.

—Jonathan Riggs

Past Fridays

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1961)

This week we went through it with Blanche & Baby Jane, & we’re telling you all this time we could have been friends. Touch up your heart-shaped beauty mark, top off your drinky poo, & toss that help-me note out the window, because we’re going there with What Ever Happened to Baby Jane in today’s Friday Feature. Published January 16, 2026.

Queens of the Dead (2025)

The end of the world is such a drag! Axe wounds, rat attacks, zombie influencers. In today’s Friday Feature, we hole up at the club & try to keep each other alive. Published January 9, 2026.

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021)

In today’s Friday Feature we’re taking the World’s Fair Challenge. Don’t at us. Published December 19, 2025.

Frankenstein (2025)

It turns out Frankenstein was the monster all along. In today’s Friday Feature JJ considers Guillermo del Toro’s endless love quadrangle. Published November 21, 2025.

Massacre at Central High (1976)

Here at CDSOB, we’ll take it any way we can get it. Today Casey Holmes takes us to school in our Friday Feature, Massacre at Central High. Published November 7, 2025.

Pam’s Night Out (Ginger Snaps, 2000)

We love Pam because she knows it’s her fault (it’s also Henry’s fault, but he doesn’t know it). In today’s Friday Feature, we revisit the tragedy of Pamela Fitzgerald in Ginger Snaps. Published October 31, 2025.